Employers, This Is Why Anonymous Surveys Are Turning Your Employees Into Little Assh*les

No, hiding behind a screen does not build psychological safety or promote "transparency"

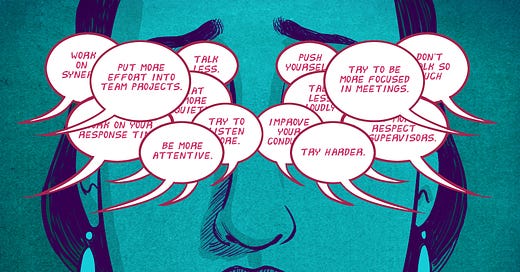

Organizational behavior clinicians, Adam Grant being one of the most widely known, remind us that creating a psychologically safe workplace is a surefire means of hacking “productivity”. In attempting to control an employee’s sense of emotional security, managerial teams opt for addressing the inevitable concerns that arise when one is forced to collaborate with different personalities, different temperaments, and different histories. To use the “official” definition of psychological safety, Google cites the concept as “feeling safe to take interpersonal risks, to speak up, to disagree openly, and to surface concerns without fear of negative repercussions or pressure to sugarcoat bad news”. The baked-in goals are logically sound, and I’d even consider them to be pre-requisites for effective communication. What’s particularly nonsensical, then, is using the anonymous survey to achieve such goals. Anonymous surveying is paraded as an objective means to share criticism without recognizing it is an unbelievably subjective experience. The privilege of staying hidden promises the use of underhanded feedback shaped entirely by opinion over fact.

Should our aim be encouraging open dialogue amongst adults, despite disagreement and diversity of viewpoint, we cannot truly believe that hiding behind a screen will suffice. I do recognize an inborn, immature streak many of us possess, the kind which seeks retaliation when we’ve been criticized or publicly humiliated. In this regard, anonymity could be useful in offering social or professional protection. What I don’t necessarily agree with is the reasoning behind such widespread use of the anonymous survey. Let’s use the first factor of psychological safety Google has provided. Interpersonal risk, although a vague concept, is the recognition and acceptance of the fair amount of risk that comes with every action we take, whether that action be social or professional. Interpersonal risks can include statements that may be misconstrued, beliefs that may be socially condemned, or suggestions that are likely to induce defensiveness. As I’ve written about on several occasions, an understanding that we cannot control another person’s reactions, understanding, personality, or general behavior should act to lubricate the discomfort of uncertainty. In continuous pursuits of quelling awkwardness by taking ownership out of criticism, we’re undermining trust--- and only increasing upon psychological insecurity.

Sane people would likely agree that continuous efforts to quell disagreement have made us both fragile and bad-tempered. A conditioned fear of confrontation is not best addressed by reinforcing avoidance through anonymous Google forms--- it is best managed through gradual and repeated exposure. Criticism, at its heart, will always be difficult to give and receive. This uneasiness does not stand as reason to avoid it altogether or to lubricate it by removing our name from it. If anything, affording employees the luxury of remaining incognito when providing criticism teaches them that we don’t trust them to handle heightened emotions. This form of “feedback” has shaped two-way anxiety: the giver is worried about upsetting the recipient, so they rely on anonymous ranking systems to curb these feelings. The recipient is afraid of hearing any form of criticism face-to-face, as they can’t rely on their ability to maintain composure, so they relentlessly read nameless criticism while trying to identify which asshole might have said it.

Invisibility, at least in the realm of performance evaluation, effectively breeds resentment and paranoia. I experienced this quite recently in an end-of-year performance evaluation, which I admittedly waited for with a bit of stage fright. Knowing I’d experienced quite a bit more sensitivity this semester than in semesters previous, I had a feeling the positive feedback would be tainted with sideswiping critique. And, I was correct! This is not celebratory, though, as I’m about to explain.

The feedback I’d received was largely centered around feelings instead of any legitimate appraisal of my professional performance. Perhaps even worse, I knew exactly who the individuals were who left such trite feedback, but I was expected to operate under the pretense that I was completely unaware. Because, with anonymous complaining, we’re not advised to approach the person we believed to have given the feedback, as they didn’t include their name and it therefore isn’t a guarantee they committed such fallacious logic in the first place. With this, then, we are to bob our heads as if we’re obtusely ignorant, burying our frustration because upper management has reminded us “even if you know who it is, you can’t know who it is, so you didn’t hear it from me”. Further, when we indulge a whiny individual by continuing to listen to baseless complaints, and proceed to play middle man by then running to the complained-about person as if they’re surely in the wrong, we reward gossip while calling it “transparency”. Why suggest mediation and face-to-face communication when we could snuggle behind the veil of tattle-taling? This is, as humor essayist David Sedaris calls it, “the golden era of tattle tales”.

The best means by which to build trust within a team is to treat them as if they’re competent individuals capable of behaving like adults who can, as the life coaches so eloquently preach, “do hard things”. I’ve seen several op-eds published related to this challenge, specifically in working with Gen-Z-aged staff: they’re in desperate need of recognition, of “check-ins”, of reassurance, and of mental health days for their increased-but-not-clinical-anxiety. There are parts of me that question the validity of anxiety-related concerns, as it’s a term as ubiquitous as “trauma” or “triggered”. We’ve undoubtedly grown more anxious more quickly, a growing theory difficult to deny when faced with mental-health related statistics. But should we succumb to today’s idiocy and call it a different form of butterflies altogether, which only encourages people to change their identity to better suit themselves socially?

With this, I’m still unsure as to why managerial staff feel compelled to indulge such emotional infancy with fully remote positions for the socially anxious, with entirely anonymous criticism for the psychologically fragile, and with a great purging of dialogue for the morally juvenile. Perhaps shifting to possible interventions, then, would be of benefit.

Modeling active listening and constructive criticism is a useful first step in promoting these skills in others. A boss highly fearful of negative reactions, as evident by G-Chatting instead of speaking and mass-emailing instead of individual consultation, is a person who condones avoidance in their own staff. Those in leadership roles must consistently learn to ask better questions and provide more thoughtful answers should they increase their staff’s willingness to do the same. Luckily, the workplace is chockfull of opportune moments for teaching: most professional circle jerks are bred on gossip and he-said, she-said.

I wrote a piece recently about how debate should replace meaningless onboarding “icebreaker” activities, as it both builds tolerance to viewpoint diversity as well as increases our ability to form clear arguments. This rings even more true for what I am alluding to with this piece. While I do believe anonymous reporting could be useful as it relates to lighthearted topics, such as deciding where the team should order lunch from or jokingly determine which staff is most likely to call in sick, I strongly contest that any form of feedback must come replete with the individual’s identity. Completely rid anonymous evaluations from your organization, as they only stand to render your employees assholes incarnate. This helps to promote ownership of our beliefs as well as fostering future conversations amongst people who have concerns with one another, which can only dampen any residual fear we have in bringing problems to light in a fair, constructive manner.

For those grandfathered into invisibility, it may be useful to start small and work up to larger, more high-stakes conversations. For the person who has only ever given and received criticism digitally, perhaps beginning a face-to-face dialogue with one person, about a fairly benign topic, is a perfect means by which to gain momentum. Clinically, this is a form of conversational systematic desensitization: our aim is to gradually dampen a heightened fear response by repeatedly exposing ourselves to the very thing which causes feelings of fear. In doing so, we habituate, or become accustomed to the sensation, which counteracts its novelty and its intensity.

Lastly, learn to radically accept that criticism is not supposed to feel good. It is built to make each of us better people, and this does not imply that we must experience positivity for positive change to occur. When the expectation is that zeal is the only accepted emotion following criticism, we cannot be surprised when staff perpetually avoid speaking with one another. In Sherry Turkle’s Reclaiming Conversation, proponents of almost exclusively-digital communication are interviewed about their preferences for online versus offline chitchat. One mother in her late forties believes that, since she’s unable to control herself emotionally when setting boundaries with her son, she feels more effective doing so through nagging and repeated copy-and-pasted text messages. Really? This is what parenting has become?

Turkle states as follows, in response to the above scenario: “Certainly this tool opens new channels of family communication. But to say to a child, partner, or spouse, ‘I choose to absent myself from you in order to talk to you,’ suggests many things that may do their own damage. It suggests that in real time, it is too hard for you to put yourself in their place and listen with some equanimity to what they are thinking and feeling. Being able to be enough in control of our feelings to listen to another person is a requirement for empathy. If a parent doesn’t model this--- if you go directly to a text or email--- a child isn’t going to learn it, or see it as a value.”

Unfortunately, digital communication isn’t only damaging to what Jonathan Haidt calls “The Anxious Generation”, or Gen-Z. It’s leaked into the conversation of everyone with a smart phone, whether that be a mother preparing to send her kids to college or a preschooler who recently learned about emojis. We cannot continue in this manner, unless our ultimate goal is to eliminate compassion or intimacy altogether. Collectively, we must argue like we’re correct and listen like we’re wrong. In doing so, we learn to support our strongest-held beliefs with legitimate evidence, and we demonstrate humility when the recipient happens to disagree. This can only enrich our current dialogue and elevate our relationships, and it can only lead to the effective collaboration workplaces are so desperate to forge.